Tour 5

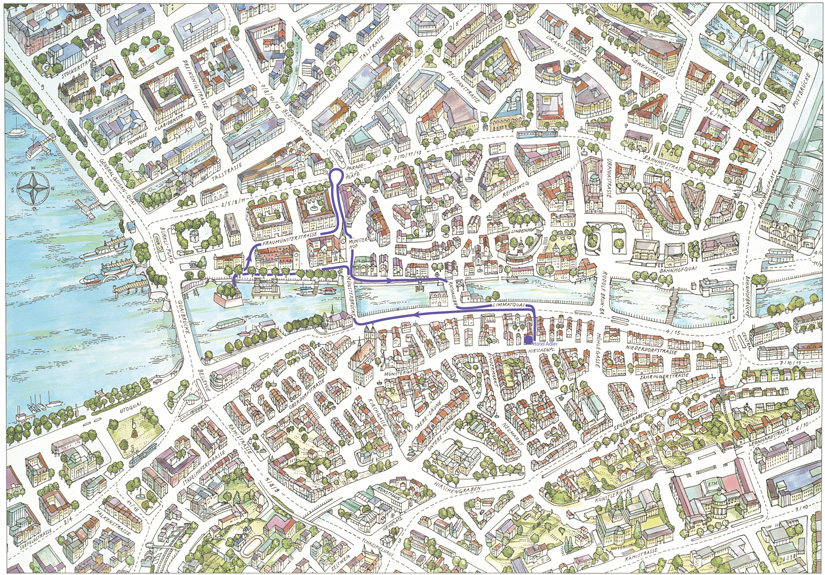

Hirschenplatz – Limmatquai – Münsterbrücke – Stadthaus – Stadthausquai – Frauenbad – Bauschänzli – Börsenstrasse – Fraumünsterstrasse – Poststrasse – Münsterhof – Wühre – Weinplatz – Gemüsebrücke – Limmatquai – Rosengasse – Hirschenplatz

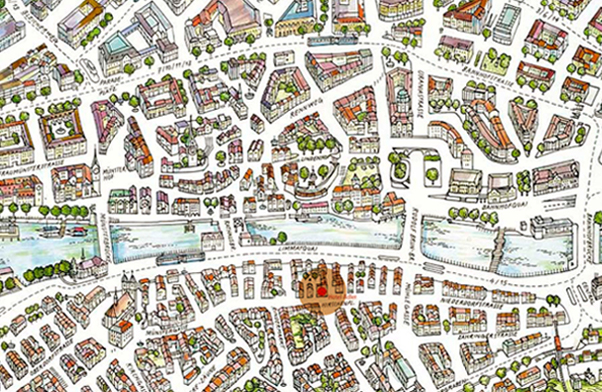

Map City Tour 5

Details: Tour 5

Part of the city administration is located in the Fraumünster district. The Stadthaus (the Town Hall) is not only where the mayor has his offices but is also the seat of the town’s executive. In addition, the joys and sorrows of the local population are recorded and filed there. In this imposing building, newly married couples, full of good intentions, start their new life together, parents register their newborn children and family members arrange a relative’s last journey. For culturally minded citizens, the Stadthaus has, since the post-war period, made a political commitment to actively promote various forms of culture such as music, literature, theatre, museums and local history. Examples of this commitment are the exhibitions that are regularly presented, free of charge, under the archways in the Stadthaus hall.

Tracing the origins of the Fraumünster abbey

Several buildings dating back to the Middle Ages and belonging to the Fraumünster abbey were located where the Stadthaus stands today. The Fraumünster church is nowadays a place of pilgrimage for admirers

of the artist Marc Chagall’s (1887– 1987) stained-glass windows. But the church also recalls the time when the Fraumünster was a convent with extensive grounds that stretched from the Münsterhof all the way to the lake. The convent was founded in 853 by King Ludwig the German and was reserved for noblewomen. In 1524, the convent was closed by the Reformer Huldrych Zwingli.

Near the Limmat, a concert hall, built in 1717 by music enthusiasts, also stood on the grounds of the former Fraumünster convent. Influenced by the sober Zwinglian spirit, the outside of the building was architecturally unassuming. The interior, however, was designed in the Baroque style, which, although not overly extravagant, created a festive atmosphere. Gustav Gull, who had just finished building the Schweizerische Landesmuseum (Swiss National Museum) near the main station, had extensive experience in incorporating historically important interiors into new buildings. Recognising the artistic importance of the concert hall’s Baroque interior, he carefully removed the precious stucco ceiling of the concert hall, which had been decorated with paintings by Zurich artist Johannes Brandenberg (1661– 1729), and transferred it to the third floor of the Stadthaus. To this day, this area of the Stadthaus carries the name “Musiksaal“ (Concert Hall).

Gustav Gull, who could be considered an early protector of historic monuments, also found a harmonious way to connect the Stadthaus with the Fraumünster church. Incidentally, the church is the sole remaining building dating from the time when the Fraumünster was an abbey. By using some original parts of the former cloister, Gull created an attractive passageway between Fraumünsterstrasse and the Stadthausquai. The walls of this passageway are decorated with frescoes depicting the history of the founding of the abbey. The frescoes were painted by Zurich artist Paul Bodmer (1886–1983) during the period between the wars as part of a municipal job-creation programme for unemployed artists.

The Stadthausquai

The Stadthausquai, with its prominent buildings such as the Stadthaus, the Fraumünsterpost (the district Post Office) and the “Metropol“ office building, is a creation of the closing years of the 19th century. It was in the Fraumünster district that the developing town first seriously undertook urban planning. When the New Swiss Confederation was founded in 1848, Zurich endeavoured to become the seat of federal power. The city fathers proposed the site of the present Stadthaus as a location for the future federal parliament. But their hopes were not realised and Berne, more centrally located, became the Swiss capital.

By 1858, it had become clear to the townspeople that the buildings of the former Fraumünster abbey as well as the idyllic Kratz district, located between the Fraumünster church and the lake, must make room for modern times. Well-known architects, among them the outstanding architect Gottfried Semper (1803–1879), were commissioned to create a new district with a spacious park and a square. A town hall was to be the centre of this new district and establish Zurich’s prestige. Although development of the lakeside area was not under discussion at the time, the planners were well aware of the district’s future prospects due to its central location and the magnificent view it offered of the lake and the Alps.

In the second part of the 19th century, Zurich’s big-city status became apparent primarily in two districts, both of which underwent changes on a massive scale. The Bahnhof district, which included Bahnhofstrasse and part of Löwenstrasse, was one and the Fraumünster district the other. The attitude of the local authorities of the time had a favourable impact on enterprises interested in the construction.

During the 1870s and 1880s, the characteristic Old-Town houses located between Fraumünsterstrasse and Bahnhofstrasse gave way to privately financed residential complexes and office buildings. However, the economically minded city authorities delayed the implementation of their own, rather farsighted plans. Although a new city administration building, now part of the Stadthaus, was constructed at the corner of Fraumünsterstrasse and Kappelergasse in 1883/1884, the Stadthaus, the Fraumünsterpost and several other impressive buildings along

the Stadthausquai were built only 15 years later, finally asserting the local authorities’ plans for the area.

The building of the Stadthaus should be been seen primarily in the political context of the amalgamation of 1893, when the following eleven municipalities were incorporated into the town: Aussersihl, Enge, Fluntern, Hirslanden, Hottingen, Oberstrass, Riesbach, Unterstrass, Wiedikon, Wipkingen and Wollishofen. The merger led to a five-fold increase in Zurich’s population. In this new situation, a large building was needed to house the central administration. But, as the population continued to grow rapidly and hence also the responsibilities of the municipal authorities, the large Stadthaus soon ran out of space. So it was that only a few years after the opening of the Stadthaus a new site for much of the city administration had to be found (see page 40).

The Frauenbad

Going for a swim in Zurich is a leisure activity that can be traced back to the 15th century. Yet, swimming in the lake or in the Limmat was for a long time the privilege of men alone. Until the 19th century, special buildings for swimming did not exist. The oldest swimming bath, designed to provide protection from prying eyes, opened in 1837 and was reserved exclusively for women. It was located south of the Bauschänzli. The present Frauenbad (swimming bath for women) on the Stadthausquai is a floating construction with four wings, featuring in the centre and at the corners wooden pavilions of a faintly oriental style. Built between 1888 and 1892, the Frauenbad is the work of then city architect Arnold Geiser (1844–1909). A similar construction, located downriver from the Rudolf Brun-Brücke, was demolished in 1950. The Frauenbad by the Limmatquai, however, was meticulously renovated and constitutes a unique architectural attraction.

Arnold Bürkli-Ziegler (1833–1894), who designed and developed the area around the lakeshore (see page 56), made the following statement: “Swimming baths are built floating on the water to make them low and unobtrusive. The facades are therefore overly long in proportion to their height…“ Floating swimming baths also have the advantage that they adjust themselves to different water levels, whereas those built on wooden pillars must take into account changing water levels. In view of the high aesthetic demands placed on the swimming baths on the lake and in the Limmat, the town council apparently sought advice from the cities of Trieste and Venice, which had already built floating pools. Trieste even put the building plans for its swimming baths at the disposal of Zurich’s town council.

Das Bauschänzli

The Bauschänzli, an artificial island in the Limmat, was built in 1660 as part of the Baroque fortifications to protect the entrance to the Limmat and defend it in the event of armed conflict. Together with the “Grendel,“ a water gate controlling access to the river, and a double row of palisades, the Bauschänzli constituted an effective line of defence between the banks of the Limmat. With the arrival of steamboats on the lake, the former military structure became simply a docking area. In 1842, the ramparts of the Bauschänzli were demolished and replaced with a parapet. The Bauschänzli then served as a public area until 1908, when the entrepreneurial landlord of the “Metropol“ building, Eduard Krug (1840– 1923), also known as “Papa Krug,“ had the original idea of setting up an open-air café on the small island.

The Bauschänzli, along with the old botanical garden at the Schanzengraben canal, is the last vestige of the Baroque fortifications. In 1642, during the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648), Zurich’s town council decided, with great reluctance and against strong opposition, to start building these massive fortifications. The fortifications were erected in response to the revolutionary change in arms technology that had taken place between 1300 and 1600, brought about by the invention of gunpowder. The medieval town wall would no longer have provided sufficient protection for the townspeople in case of an attack. The towers could not accommodate heavy guns and the town walls would not have withstood enemy artillery for long.

The building of the star-shaped fortifications around the town provided protection and also created space for further developments. Thus, in the 17th and 18th centuries, Baroque settlements were built in the areas of Talacker and Stadelhofen. Regrettably, most of the houses in these areas, which were often of cultural and architectural importance, fell victim to the economic developments of the 20th century.

Already in 1833, the great council of Zurich (today known as the cantonal council) decided to level the fortifications around the city. From a military point of view, these defensive structures had lost their importance, and politically they were an unwanted symbol of the city’s dominance over the surrounding countryside. The fortifications were also an obstacle to traffic, especially in a time when trade and travel was becoming more important.

The “Metropol“ building

The Börsenstrasse (stock exchange street) recalls the time when Zurich first became important as a financial centre. The first stock exchange was opened in 1880 at Bahnhofstrasse no. 3. The “Metropol“ building, whose main entrance is at Börsenstrasse no. 10, merits special attention since it constitutes one of the most elegant architectural designs of the closing years of the 19th century. This office complex, in fact composed of five adjoining buildings, stands as a witness to the changing building techniques and the stylistic freedom of the era called the “Belle Epoque.“ The construction of the “Metropol“ complex, which was completed in 1893, introduced the use of standardized and prefabricated components in the building process. The inside of the large building could be subdivided and adapted according to the wishes of the tenants as long as this revolutionary freedom of structure was not limited by supporting walls or firewalls. On the facades, stone pillars were the only visible supporting elements. Glass panels and iron components were fixed between these stone pillars. The ground floor passageway, located under arcades, recalls the building style of the Italian High Renaissance. On the upper floors, however, a Baroque influence can be seen. As well as various shops, the legendary “Grand Café Metropol“ was located on the ground floor of the large building. It offered room for up to 600 people and guests could choose whether they wished to spend their time in the café, the dining room, the pub or the billiard room. But, the “Grand Café“ atmosphere is long gone and the “Metropol“ building now houses the municipal tax offices, which, incidentally, will move out of the premises in the not too distant future. All that is left of the original interior design are the decorative stairwells, which were renovated between 1988 and 1992, as were the facades and the roof.

Heinrich Ernst (1846–1916) was the entrepreneur who both built the “Metropol“ and drew up the plans. Among other buildings, Ernst designed the magnificent “Rote Schloss“ (Red Castle) on the General-Guisan-Quai. A successful financier for decades, Ernst fell victim to speculation during the property crises of 1900 and ended his days in poverty and piety.

The Poststrasse

In 1838, Zurich’s post office building was moved from Münstergasse to Poststrasse. With increased trade and travel, the town found it necessary to build a modern, spacious post office building outside the narrow confines of the Old Town. The site chosen was perfectly located for the circumstances of the time because of the nearby Bauschänzli, which had served as a landing stage for steamboats since 1835. Thus, the Fraumünster district became something of a traffic junction. Towards the middle of

the 19th century, there was even talk about moving the train station

to Paradeplatz in order to better coordinate the different means of transport such as stagecoaches, trains and steamboats.

The well designed post office complex, which included an administrative building, stables, coach-houses and watering places for horses, covered approximately the same area as the present-day “Zentralhof.“ About 30 stagecoaches passed through the Poststrasse each day, making for a lively atmosphere. Express stagecoaches served all the major destinations within Switzerland. Also, journeys to and from Bavaria, Saxony, Prussia, France, England, Italy, Spain, Austria or even Turkey started or ended in the Poststrasse.

Many native and foreign guests passing through Zurich stayed in the Hotel “Baur en Ville“ (Savoy), located opposite the post office complex. Between 1837 and 1876, the “Tagblatt der Stadt Zurich,“ the local newspaper, published the names of the bourgeois or sometimes even aristocratic guests in town, providing topics for conversation and opportunities for contacts.

When the post office complex opened, nobody could imagine that the success of the railway would only a few decades later bring about the end of the stagecoach era. Yet, about 35 years after it opened, the post office building was closed, and in its place, the “Zentralhof“ was built between 1873 and 1876, including 15 residential and office buildings.

The Münsterhof

The Münsterhof is the largest Old Town square on the left bank of the Limmat. The square appears for the first time in documents dating from 1221. A survey of the square’s history reveals its changing role. During the Middle Ages, it was where the stonemasons worked. In 1504, the Münsterhof was the stage for a passion play that was recorded in the town chronicles as “das Schicksal der Zürcher Stadtheiligen Felix und Regula“ (the fate of Zurich’s patron saints Felix and Regula). Also, the cattle and pig markets were held in the square until 1667, and from 1627 onwards, permanent market stalls were located there too. From 1701 to 1796, the spring and autumn trade fairs took place every year in the Münsterhof, transforming it for a few days into an especially busy place full of merrymaking. But the square has served as a place to celebrate special occasions and festivals even in recent years. For example, Winston Churchill greeted the cheering crowds from the balcony of the “Zunfthaus zur Meisen“ in 1946.

The two guild houses are a reminder of the period between 1336 and 1798, when Zurich’s political and economic power lay in the hands of the various guilds. Since the guilds wielded so much power and influence, they competed with one another to build the most magnificent guild house located in the best, most central position. The guilds’ political influence came to an end with the fall of the “Ancien Régime“. In the following era, characterised by republican values, the guilds soon played a new role as the successful organisers of the Sechseläuten. The Sechseläuten (ringing of the bells at 6 p.m.) is Zurich’s yearly spring festival, celebrating the arrival of spring with a superb procession. The festival gives Zurich the opportunity to present itself in a festive mood and, above all, to take pride in its history and traditions. During the Sechseläuten, a procession with 3000 men dressed in traditional guild costumes, hundreds of horses and countless decorated floats representing scenes from the past, winds its way through the streets of the city centre. The colourful procession gives the impression that time has been turned back.

Reviews

Barry S

Google, 19.8.23

Very nice boutique Hotel. Convent to the main station and tram 4 . Maybe a ten minute walk . ( we walked upon arrival ) In a nice area of old town with many shops and restaurants steps away . Easy check in . They have complimentary water and drinks . Museum access that we took advantage of . Our room was on the top floor with a balcony . Would not consider staying anywhere else .

Sarah B

TripAdvisor, 19.8.2023

Nice location, even better people!

Anne Clarisse V

Google, 5.9.2023

Spent my birthday here and it was lovely. The fondue and raclette tasted amazing! And the staff was very friendly. They also sang happy birthday and brought out an ice cream dessert with a sparkler.

David S

TripAdvisor, 2.9.2023

Cheese fondue heaven.

Our Location

Hotel Adler Zürich

Rosengasse 10

CH-8001 Zurich

+41 44 266 96 96

info@hotel-adler.ch

Our front desk is available 24/7

Reviews

Our Partners

© Hotel Adler Zürich | Imprint | Terms & Conditions | Privacy | Voucher | Covid-19