Tour 4

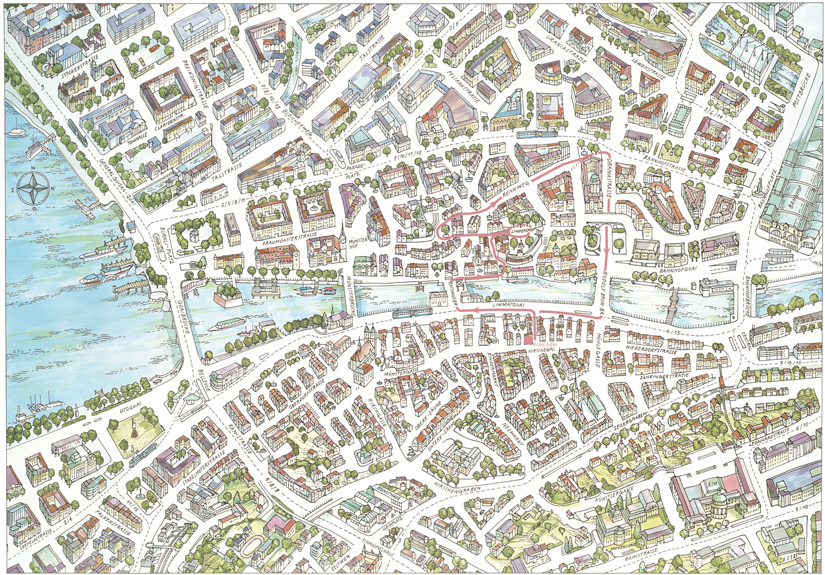

Hirschenplatz – Rosengasse – Limmatquai – Rathausbrücke – Schipfe – Wohllebgasse – Lindenhof – Strehlgasse – St. Peterhofstatt – Rennweg – Bahnhofstrasse – Uraniastrasse – Rudolf Brun-Brücke – Limmatquai – Rosengasse – Hirschenplatz

Map City Tour 4

Details: Tour 4

The peaceful Lindenhof, located on a small hill by the Limmat, is a perfect place to begin the journey through Zurich’s 2000-year history, since the site offers a view stretching from the Old Town to the districts that were once beyond the city limits. If the pre-historic settlements on the lower part of lake Zurich and the few Celtic discoveries on Rennweg are overlooked, the Lindenhof represents the real birthplace of the town. In 15 B.C., after a military campaign that had led them across the Alps, the Romans built a small customs post in this spot. The post allowed them to control a bridge, which spanned the narrowest part of the Limmat at the bottom of the hill. By the time the Roman Empire had reached its peak, the small customs post had become a fortress with towers and gates that could be seen from afar. But it was not until a Roman tombstone was unearthed in 1747 that the Roman name for the town was rediscovered: Turicum. During the Middle Ages, a feudal castle was built on the ruins of the Roman fortress. However, this castle did not survive long, much to the satisfaction of the town’s bourgeoisie and clergy, who were striving for social progress.

The Lindenhof

Although the Lindenhof is above all a reminder of the Roman period, the view it offers provides information about Zurich’s various developmental periods. From the Lindenhof, the medieval town boundaries, once reinforced by town walls and observation towers, can still just be identified or at least imagined. A look at the town model displayed in the “Haus zum Rech“ at Neumarkt no. 4 (see page 17) certainly helps one to picture the medieval town. But it is much more difficult to imagine the large areas adjacent to the star-shaped fortifications that constituted a second line of defence. The17th century saw the establishment of new Baroque settlements with beautiful French gardens in the Talacker and Stadelhofen districts. The Schanzengraben, formerly a part of the defensive structures and now a canal, has survived, although in a much altered state.

When the fortifications were demolished in the early 19th century, the town, endorsing the new liberal ideas of the time, used the newly gained land for new building projects. The Federal Institute of Technology, the cantonal hospital, the first cantonal school and an old people’s home were built on the land that in the past had formed part of the fortifications. These institutions constituted only a few of the many that were created during this era of liberalism. In 1893, eleven adjacent villages, already organizationally and economically linked with the town, were also incorporated politically.

A further eight independent municipalities became part of the town in 1934.

The Peterhofstatt

St. Peter’s church is the oldest parish church in Zurich. According to archaeologists, a Roman temple originally stood on the same site. The lower part of the prominent church tower dates from the 13th century.

In later years, improvements were made to the tower, and in 1534, four clocks with enormous faces were added. The clock-faces, which can be seen from afar, are at 8.7 m diameter the largest in Europe. The shingle roof features four oriel windows, which provide a clear view over the houses of the Old Town. Until early in the 20th century, a watchman, whose responsibility it was to raise the alarm in case of

fire, sat up in the tower.

The church’s large nave with its galleries and wide arches was built in 1705 in the Baroque style, replacing an older building. Bold stuccowork and elegant, richly decorated marble columns bear witness to the joyful spirit of the time. When St. Peter’s church underwent extensive renovations in 1974, its facade regained its original colouring, a pleasant blue tone, which makes the church stand out from the others buildings around the Peterhofstatt (the square in front of the church).

The Peterhofstatt commemorates two of Zurich’s important public figures. But in accordance with Zurich’s often rather reserved manner, no imposing statues were erected to honour these men. Rather, a simple gravestone, standing discreetly by the church facade, commemorates Rudolf Brun (circa 1300–1360), the first, all-powerful mayor of Zurich, who was elected for life. In 1336, Brun overthrew the town council, which at that time was controlled by rich noblemen and merchants, and created the guilds. Thus, he was the founder of the guild institution, which played a dominant role in the political and economic life of Zurich up until the French invasion in 1798 (see page 52).

Directly opposite Brun’s gravestone, a simple inscription at St. Peterhofstatt no. 5 honours the enlightened philosopher Johann Caspar Lavater (1741–1801). Lavater was a minister at St. Peter’s church and author of philosophical works. His book “Physiognomische Fragmente” made him a celebrity. The parish hall at St. Peterhofstatt no. 6 houses the room where Lavater did most of his work. One of Lavater’s most famous guests was Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who, in 1779, was accompanied by his protégé, the duke Karl August von Weimar (see page 35). During the French occupation, Lavater was shot by a French soldier and subsequently died of his wounds.

The city administration buildings

Zurich’s town centre surprises the visitor with its contrasting building styles. A walk from the idyllic St. Peterhofstatt to the rather elegant Bahnhofstrasse, via Rennweg with its small-town atmosphere, will clearly illustrate this. Whereas the Bahnhofstrasse reflects the spirit of the Gründerjahre (the 1870s and 1880s), Uraniastrasse, with its eye-catching tower housing the Urania observatory, announces the 20th century. The Urania office building and the adjoining observatory were built between 1905 and 1907. The name Urania was chosen in memory of the Greek Muse of Astrology. The co-operative that built the Urania complex intended to rent out office space to finance operations of the first public observatory in Switzerland. The observatory, situated in the dome of the tower, opened on June 15, 1907. The telescope, built by Carl Zeiss in Jena, is equipped with a colour-corrected double lens 30 cm in diameter, with a focal length of 500 cm, and it allows up to 600-fold magnification. The observatory flourished in the 1920s; however, during the following world economic crisis, it was not only threatened with closure but even the demolition of the tower was envisaged. In 1936, Zurich’s Volkshochschule (adult education institute) proposed the establishment of the “Gesellschaft der Freunde der Urania Sternwarte“ (Society of the Friends of the Urania Observatory), which undertook to cover any financial losses. To this day it is the Volkshochschule which acts as patron of the popular observatory.

At the time of its construction, the impressive octagonal Urania tower, at a height of 50 m, was the tallest building in Zurich. The imposing building was part of the reorganisation of the Werdmühle und Oetenbach districts. In order to build the Uraniastrasse, a traffic artery linking Sihlporte, the Rudolf Brun-Brücke and Mühlegasse, the picturesque Werdmühlekanal had to be filled in and the entire Oetenbachhügel levelled. This work was undertaken at the beginning of the 20th century. The Oetenbach convent, which last served as a cantonal prison, also fell victim to this massive intervention in the topography of the inner city.

The creator of this new, generously laid out area was Gustav Gull (1858–1942). Gull, whose name has gone down in the history of Zurich as city architect and professor at the Federal Institute of Technology, not only built the Urania office complex with the adjacent observatory and the imposing Werdmühle office build-ing dominating Werdmühleplatz, but also the city administration buildings located above Uraniastrasse on the Lindenhofbrücke. Incidentally, only a part of the original building project was actually realised. The plan was to construct an entire administration district featuring a large central building above the Uraniastrasse. The highlight was to be the construction of a tower 90 m high. Furthermore, the plan called for demolition of the row of houses along the Schipfe and construction, in their place, of two-storey market halls with arcades. Gull had conceived of an enormous flight of stairs that would have led down to the Limmat river. As his still existent drawings show, this would have created a distinctly Venetian atmosphere.

However, world history intervened. The outbreak of the First World War brought the colossal building project to a standstill. The years of crises that followed further contributed to the end of this architectural dream. Nevertheless, Gull’s influence on the cityscape has been enormous. His creations include the Stadthaus (the New Town Hall), the Schweizerische Landesmuseum (Swiss National Museum), the tower of the Prediger church and the expansion of the Federal Institute of Technology with its monumental dome.

Remembering the Mühlestege

The Rudolf Brun-Brücke (Rudolf Brun Bridge) and the Mühlesteg (Mill Foot Bridge), situated further downstream, recall the Limmat area as it looked in the past. The present iron Mühlesteg was constructed as a footbridge in 1981. It links the right bank of the Limmat, the Limmatquai, with the left bank, the Bahnhofquai, and its name indicates the historical role of the part of the Limmat located between Rudolf Brun-Brücke and Bahnhofbrücke. Here, where the river is wide and today flows freely, there existed two narrow bridges: the Untere Mühlesteg, located upstream from the present Bahnhofbrücke and the Obere Mühlesteg, situated downstream from the Rudolf Brun-Brücke. Written sources dating from the Middle Ages indicate a third Mühlesteg, in approximately the same place as the present footbridge. During the Middle Ages, the townspeople used this part of the river to drive their mills, which stood on piles in the riverbed. Centuries later, during the Industrial Revolution, substantial factories, also dependent on water-power, were erected in place of the old mills as were houses, which often served as businesses and dwellings.

Until well into the 20th century, these picturesque houses shaped not only the Limmat area but also the appearance of the town as a whole. There were various reasons for the demolition of the historical Mühlestege: their bad structural condition, the fact that they could not accommodate horse drawn-carriages nor automobiles in later years, and the spirit of the time, which did not attach particular importance to the preservation of historic monuments. In addition, the decision to demolish the footbridges and the buildings was also decisively influenced by the technical need to regulate the water level of Lake Zurich. This project was primarily achieved by the installation of a weir further downstream, level with the Drahtschmiedli, and by the construction of the Lettenkanal. The result of these changes was a rise in the water level of the Limmat, and this in turn led to the demolition of most of the buildings near the foot bridges in the 1930s. In 1943, the last building standing in the area of Limmatquai/Rudolf Brun-Brücke was pulled down and in 1951, much to the regret of the local population, the well loved covered wooden bridge near the Bahnhofquai was also demolished.

In contrast to the changed appearance of the Limmat area downstream of the Rudolf Brun-Brücke, the area upstream of the bridge still testifies to its historical past. The towers of the Old Town’s four churches dominate the skyline and soon become familiar to visitors. On one side of the Limmat is the bustling Limmatquai and on the other side, lining the quiet Schipfe, stand the harmonious houses that luckily escaped demolition when Gull’s building projects were brought to a standstill. And above the Schipfe, the welcoming Lindenhof, with its many trees, overlooks the Old Town.

Reviews

Barry S

Google, 19.8.23

Very nice boutique Hotel. Convent to the main station and tram 4 . Maybe a ten minute walk . ( we walked upon arrival ) In a nice area of old town with many shops and restaurants steps away . Easy check in . They have complimentary water and drinks . Museum access that we took advantage of . Our room was on the top floor with a balcony . Would not consider staying anywhere else .

Sarah B

TripAdvisor, 19.8.2023

Nice location, even better people!

Anne Clarisse V

Google, 5.9.2023

Spent my birthday here and it was lovely. The fondue and raclette tasted amazing! And the staff was very friendly. They also sang happy birthday and brought out an ice cream dessert with a sparkler.

David S

TripAdvisor, 2.9.2023

Cheese fondue heaven.

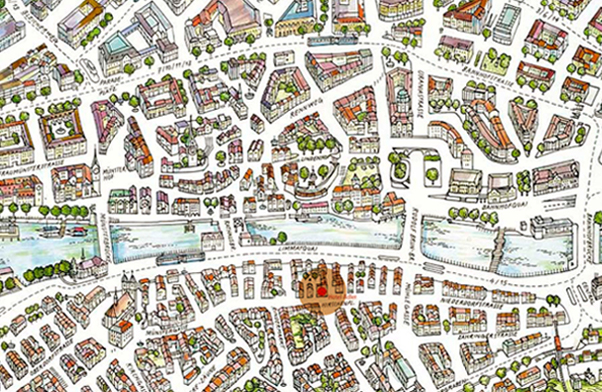

Our Location

Hotel Adler Zürich

Rosengasse 10

CH-8001 Zurich

+41 44 266 96 96

info@hotel-adler.ch

Our front desk is available 24/7

Reviews

Our Partners

© Hotel Adler Zürich | Imprint | Terms & Conditions | Privacy | Voucher | Covid-19